Is it business as usual for ocean carriers as they continue to buy large vessel assets? In a rapidly changing market, it is important that shipping lines have sufficient liquidity to pay for assets that some would argue are, in certain cases, not even required.

The mid-term health of the container industry is an unknown right now. While we have covered the potential cost impact of IMO 2020 in a previous article, the position is made more opaque by what may happen as a result of the industry’s mini-ordering boom, itself partly engendered by IMO 2020. The correct way to safeguard future financial security remains unclear, however, simple reasoning dictates that shipping lines must ensure their future commercial pricing strategies are more successful and that they secure profits to cover significant increased CAPEX.

What goes around, comes around

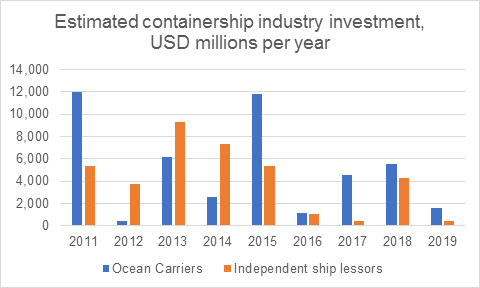

Some would argue that the industry has not yet recovered from the last ordering boom of 2015, when shipping lines spent an estimated USD 11.8bn on 1.3m TEU of capacity. About 500,000 TEU of this is still to be delivered (suggesting that final payments of around 20% need to be paid to the shipyards during 2019). After two lean years of ordering, an estimated USD 9.8bn was spent on new container vessels during 2018, primarily for delivery during 2019 to 2021. 56% of this figure (USD 5.5bn), or 675,000 TEU of new capacity, is for the direct account of ocean carriers. A small amount of this figure may be recouped through scrapping smaller vessels, but the majority of the largest vessels are not for the renewal of aged vessels. This year has been quiet so far but, barring sale/leasebacks at a later date, two of the three big orders in 2019 have been directly for the account of shipping lines: CMA CGM for 15,500 TEU vessels and Sinokor Merchant Marine for feeder vessels.

So what?

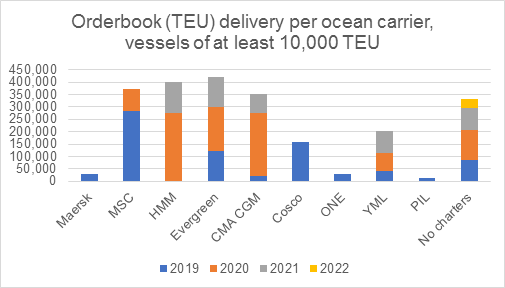

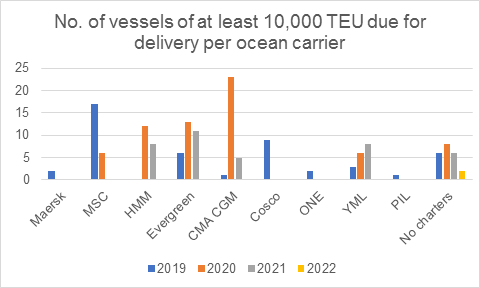

While some analysts regard the orderbook, currently standing at only about 13% of the current global fleet, as small, we would argue that this misses the point. The financial burden of such CAPEX is huge, and the fact that the orderbook is top-heavy with ships of 10,000 TEU and above means that their deployment is made more difficult across relatively fewer trade lanes. The ongoing cascade of larger vessels from the primary East-West lanes to smaller routes means that there are fewer options to place large ships without damaging the prevailing supply/demand balance.

It must also not be forgotten that ocean carrier revenue from freight rates has been perennially poor in most years since the 2008/2009 global economic crash. The number one liner operating group by capacity, AP Moller-Maersk, just reported a USD 220m underlying profit for full-year 2018, during a year when global cargo growth remained robust at around 4-5%. However, the financial statements of many liner companies repeat the general trend that despite growth in volumes, average freight rates per container are in decline, while operating costs are also increasing.

Over and above the risk generated by the newbuilding orderbook, ocean carriers could fare poorly again this year in their Trans-Pacific rate negotiations with beneficial cargo owners, which may baulk at bunker clauses that are sufficient to cater for the liner companies' increased fuel costs, expenditure on retro-fitting scrubbers, and preparation for the purchase and trial of new low-sulphur fuels from late 2019.

Alliance discrepancies

At an individual asset size level, the orderbook highlights that nearly 79% of capacity (2.17m TEU and 135 vessels) is for vessels of at least 10,000 TEU — which could be increased by another 10 vessels if we include the new order for 15,500 TEU units (yet to be officially confirmed by CMA CGM). These vessels are currently too small for the Ocean Alliance (of which CMA CGM is a founding member) to deploy on the Asia to North Europe trade lane and should they be deployed in the Asia to Mediterranean or Trans-Pacific trades, they will release another string of 11,000 TEU vessels via the cascade. A simple question to ask here is, does CMA CGM need these vessels to cater for future demand growth and even more so as a member of the Ocean alliance, which currently has the largest orderbook amongst the three main operating alliances? CMA CGM currently has USD 8bn of long-term debt, which could be increased by an estimated USD 1.2bn should the new vessels be confirmed for its own account, rather than on a long-term deal through a major asset leasing partner.

Adding in the fact that there are another 22 vessels (330,000 TEU) which appear to have been ordered with no long-term charters attached, this could mean further disruption on the supply/demand front, depending on who eventually deploys them, and where.

What now?

We could say in fairly simple terms that the major liner operating companies will have an increased commercial requirement to fill evermore slots across their core deep sea container routes — which at the moment have major question marks against them on the demand side.

History tells us that ocean carriers have fought fiercely with each other for market share, and so if the current order book does bring about similar declines in freight rates, shipping lines need to look at other ways to secure revenue, or reduce costs. In addition to the adjustments to the BAF discussed in our earlier blog, major carriers have announced major cost-reduction programmes, increased digitalisation, and diversification into door-to-door logistics capabilities (CMA CGM via its recent equity interest in CEVA Logistics, and AP Moller-Maersk investing through its freight forwarding division, Damco Transport).

However, it could be argued that some of the Asian operators and asset lessors are on the verge of repeating the same mistakes of the past by ordering capacity that is not required and that they are ill-equipped to fill at market compensatory levels. While a company initiating CAPEX while simultaneously posting losses is not unusual, HMM’s recent vessel order for 20 large container vessels worth USD 2.8bn when it recorded a net loss of USD 535m for the first nine months of 2018, would appear to be a case in point. With HMM unlikely to be an isolated case, a careful watch is required on the bottom lines of its peers.

Infospectrum is regularly reviewing the counterparty risk of large and small players in the liner sector. If you would like to discuss this sector further, click the button below to get in touch.