A carbon-free maritime sector may seem a distant prospect, but the largest liner operators are aready making plans to comply with regulatory measures well in advance of the key 2050 deadline. However, many questions need to be answered and challenging decisions need to be made.

The liner sector may be considered by some as one of the smaller components within the broader maritime decarbonisation movement, given its relatively small total fleet size when compared to the dry bulk and tanker sectors. However, its small number of prominent operators are proactive on this huge issue. As the carriers of virtually all our daily consumer goods, they are very much in the shop window, and while the regulatory aim of a carbon-free maritime sector by 2050 may seem well distant today, decisions on vessel newbuilding orders and fuel types are having to be to be made now. A global liner sector fleet of around 5,400 vessels clearly consumes an enormous amount of bunkers. And to put this into perspective, Maersk, the largest shipping company in the world (with a fleet of over 700 vessels), consumed 10.3 million tonnes of fuel in 2020 at a total cost of USD 3.84bn. The latter figure would of course have been considerably higher had it not been for the disruption brought on by the effects of COVID-19. Estimates also suggested that container vessels accounted for around 30% (or about 184m tonnes) of global shipping industry CO2 emissions in 2019.

The need to decarbonise is gaining more traction in the maritime world, with a coalition of major charterers (including high-profile companies such as Cargill, Bunge, Louis Dreyfus, ADM, Trafigura, Shell, Norden, Torvald Klaveness and others) launching the Sea Cargo Charter framework in October 2020 to assess and monitor ongoing greenhouse gas emissions in the maritime supply chain. It is assumed that many more companies will sign up to the charter, and member operators will need to be increasingly transparent in terms of how they are improving emissions and meeting ongoing regulatory requirements.

As it stands, IMO regulations require all vessels to be compliant with 0.5% sulphur emissions, but new proposals requiring vessels in all sectors to meet more stringent operational efficiencies and carbon intensity are being pushed through to take effect from 2023, and so the operating environment continues to change. As of January 2021, about 915 container vessels were fitted with scrubbers (meaning they continue to have the option to use high sulphur fuel oil ‘HSFO’), with the vast majority of the remaining fleet using very low sulphur fuel oil (‘VLSFO’). While liner operators enjoyed low VLSFO prices for much of 2020, they will be wary that the average Rotterdam price in May 2020 of USD 190 per tonne currently stands at around USD 470 per tonne. However, sharp cyclical movements in the oil industry are not uncommon, and they will continue throughout the transition of the maritime industry to its ultimate aim of carbon-neutrality. Will these price developments primarily drive future decisions regarding choice of fuels and engine configurations?

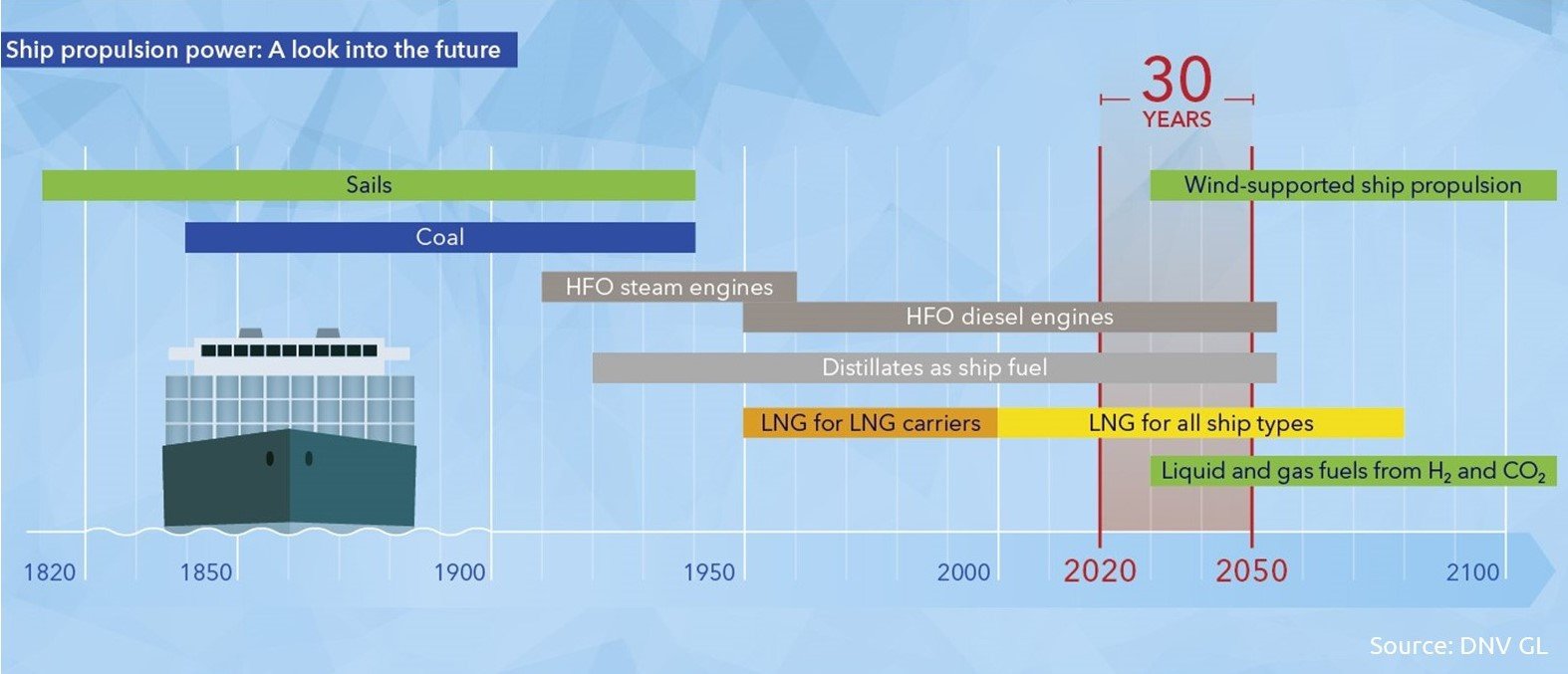

Indeed, many ship owners and operators continue to look at the decarbonisation movement as a cost issue, and as such, often delay strategic decision making – ultimately the approach taken with regard to decarbonisation does not just lie in using VLSFO or burning HSFO with the use of scrubbers. These are interim measures only, and much more work is needed. Given what is happening in the automotive world, where diesel-fuelled cars will no longer be made by most European car manufacturers in the near future, the continued production of IFO 380 on a global level will presumably be near-term only. Any stakeholders (particularly ship operators/owners) thinking that they can start to make decisions in early 2049 because they do not want to consider potential additional costs in the interim, will have a big shock in store.

Most ship owners view the lifetime of vessel assets to be 20 to 25 years, but even newbuildings in the pipeline today may potentially have a much shorter lifespan given that the choice of fuel type is so paramount. At the very least, costly vessel retrofits in terms of new engines (from a very small number of manufacturers) and additional specification are likely to be required. And these vessels will then be temporarily taken out of the supply chain, but at what additional costs for shippers and consumers in terms of delays? Hence, a co-ordinated approach is required with the oil majors and bunker suppliers involved at an early stage. Remember, meeting global decarbonisation measures as a part of the climate movement are not solely incumbent on the fuel users, but the fuel manufacturers and suppliers too.

What are some of the key questions and considerations for stakeholders in the container sector?

For owners/operators:

- What type of fuel should be utilised (biodiesel, methanol, ammonia, LNG, hydrogen, and other forms of biomass or renewable power)?

- Renewal of fleet, investment decisions? Which shipyards?

- Vessel specification, engine type for shipyards?

- Financing (European banks/financiers are already insisting on so-called “Green loans” only)

- Ensuring a global supply of fuel at all key locations and from which suppliers?

- Increased credit lines from fuel suppliers

- A change to new suppliers, and building new commercial relationships?

- Cost versus any potential backlash from shippers/clients as part of their Sustainability standards and requirements

For fuel suppliers:

- Research into new fuels

- Meeting of fuel standards which will evolve over time

- Meeting individual fuel capacity and requirement levels, including storage (in co-ordination with oil/energy majors). This largely depends on which fuel(s) operators use, which remains undecided

- Investment in new bunkering vessels?

- Meeting geographical fuel availability levels

- Deal with fuel stability and compatibility challenges

To date, most of the top 10 global liner operators have embraced decarbonisation. Not only are they in the shop window, but they have large operating fleets and seemingly decisions should not be delayed given the clear cost implications. In addition to Maersk’s huge fleet, MSC has a current fleet of about 590 vessels, CMA CGM (560), COSCO (500), Hapag-Lloyd (250), Ocean Network Express (230), and Evergreen (200). And the majority of these vessels are large boxships.

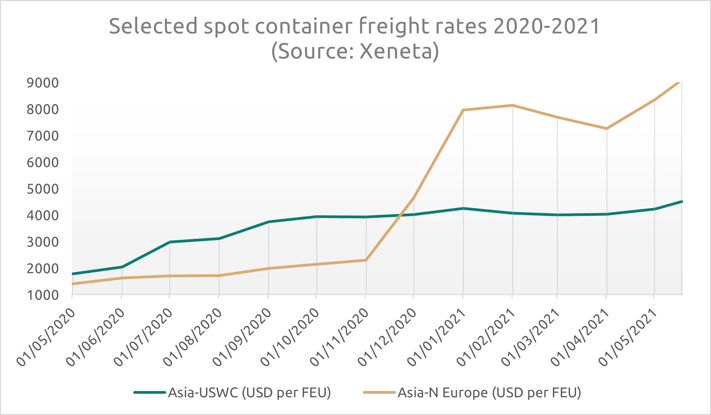

Despite the negative impact of COVID-19 in 1H 2020 on global cargo volumes, the container sector has been red-hot since about July 2020, with freight rates, revenue and profits all rapidly heading north for the key operators, to historic highs. The graph below charts the freight rate developments on two core trade routes during this time frame, highlighting that they have reached record levels in under 12 months. This has encouraged many industry players to embark on substantial newbuilding commitments, but most have a firm eye on the future. Maersk recently announced its intention to deliver the world’s first carbon neutral liner vessel by 2023. The 2,000 TEU vessel will reportedly operate on standard VLSFO, although the plan is to eventually utilise either e-methanol or bio-methanol. Hamburg and Singapore-based owner Asiatic Lloyd has recently ordered two conventionally-fuelled 7,100 TEU containerships from a Chinese shipyard that are classed as “ammonium-ready”. However, by way of warning, a previous attempt by Hapag-Lloyd to convert an “LNG-ready” vessel to LNG, proved to be uneconomic.

This aside, CMA CGM has already championed the use of LNG, with its series of 23,000 TEU newbuildings all geared towards this fuel-type, and a global supply-chain deal extended by French oil major Total in the bag. The company has just placed another order for 22 vessels which includes 12 units (of 13,000 TEU and 15,000 TEU capacity) that will also be configured to run on LNG. However, not all liner operator majors and wider sector stakeholders see LNG as the future fuel (it is seen by some more as an interim measure, and as a fossil fuel, emits harmful methane). MSC is exploring the hydrogen route, and more recently has joined a global initiative led by the Hydrogen Council. Ocean Network Express recently trialled the use of biofuel with a sustainable fuel manufacturer called GoodFuels. Hapag-Lloyd’s most recent order for 24,000 TEU newbuildings comprises vessels with dual-fuel capability; the company has also tested a biofuel based on cooking oil. The larger Asian-based liner operators (Evergreen, HMM, Yang Ming, and COSCO) have been noticeably quiet concerning their future strategies. However, this still proves that the leading bunker suppliers/producers need to maintain their current active research levels into alternative fuels and viable solutions in order to ensure that they are future-ready for the energy transition.

A number of the vessels in the current orderbook have a dual-fuel specification and so companies are hedging their bets, but it remains unclear if the dual-fuel caters for the new range of fuels on the horizon such as hydrogen, methane and ethanol.

Of course, there are so many questions to answer, but liner operators are starting to look at these in earnest. The leading liner operators could be considered as amongst the first taking steps to fulfil decarbonisation aims. But whatever sector you trade in, you are all part of this process, start engaging, and everyone (primarily shippers) will have to come to the party to a degree in terms of paying for the “new maritime world”.

Infospectrum has the largest Databank of shipping and commodities risk appraisal reports in the industry. View our latest reports by clicking the link below: