Container rate fundamentals have remained solid so far, but future western demand and its supply chain handling ability is a serious concern.

Any impact assessment of the effects of the COVID-19 virus outbreak must concern supply and demand, but for the container industry, this is made more difficult given that this has coincided with the significant seasonal impact of the Chinese New Year holidays. In 2020, the holidays began on 25 January, with the usual shutdown of factory production in China lasting for 10-14 days. With the additional impact of COVID-19, it is very difficult to determine the relative impact of each on the sector, since one event has immediately overlain the other.

Supply and demand

The downturn in factory production in China (as a direct result of migrant workers not returning from their homes after the Chinese New Year holiday) has led to a significant impact on all China export trades since early February 2020. The decline in the number of containers carried is not yet known, although isolated data points from key ports are giving an indication of the immediate impact. The collective volume (imports and exports) of China’s top eight container ports reportedly declined in February by 19.8% year-on-year (although as stated, this is not unusual for February). Another key indicator is from the port of Los Angeles (a major US transpacific port) where loaded imports in February 2020 have fallen by 22.5% year-on-year.

On the supply side, with significantly less cargo to load from China, all container operators have increased their blanked sailings (whereby a container vessel is temporarily idled for one round-trip voyage in an effort to align trade capacity with a decline in cargo). Indications are that 33 individual sailings had been cancelled on routes to Europe by main line operators in the four-week period to early March 2020. If the core transpacific trade lane is added in, an estimated 30% or more of weekly outbound capacity has been removed from the market, and many more blanked sailings are still planned on major headhaul trades from now into early May.

A major factor which has complicated the impact assessment is including the number of vessels awaiting scrubber retrofits (due to the IMO’s low-sulphur fuel regulations effective from 1 January 2020). As of late February 2020, some 111 container vessels (with a total capacity of 1.02m TEU), including 83 vessels at Chinese yards, were still undergoing retrofits, with the average length of stay reported to be about 55 days. The virus impact has led to extended stays for some vessels, with MSC ships said to include 33 of this total. If idled vessels from liner blanked sailings are added to this total, then as of 2 March, a reported 402 vessels, with a total capacity of 2.46m TEU, were classed as being inactive. This equates to approximately 10.6% of total industry capacity, a figure which has not been experienced by the industry since the peak of the 2008/2009 global financial crisis.

Container rates

With such a dramatic impact in container volumes across key headhaul trade lanes from Asia, a significant decline in freight rates would have been expected. However, this has not happened, as the spot freight rate data from the Shanghai Containerized Freight Index (SCFI) in the table below illustrates.

|

|

Shanghai / N Europe (USD / TEU) |

Shanghai / West Med (USD / TEU) |

Shanghai/ USWC (USD / FEU) |

Shanghai / USEC (USD/ FEU) |

Shanghai / Dubai (USD / TEU) |

Shanghai / Melbourne (USD / TEU) |

|

As at 16/03/2018 |

741 |

665 |

1,016 |

2,009 |

384 |

933 |

|

As at 15/03/2019 |

714 |

748 |

1,345 |

2,357 |

590 |

358 |

|

As at 13/03/2020 |

827 |

903 |

1,610 |

2,912 |

1,009 |

771 |

|

2019/2018 y-o-y |

-3.6% |

12.5% |

32.4% |

17.3% |

53.6% |

-61.6% |

|

1 Jan to mid-March 2109 vs 2018 comparison (ytd) |

2.5% |

19.9% |

30.4% |

12.8% |

36.8% |

-60.3% |

|

2020/2019 y-o-y |

15.8% |

20.7% |

19.7% |

23.5% |

71.0% |

115.4% |

|

1 Jan to mid-March 2020 vs 2019 comparison (ytd) |

4.3% |

19.0% |

-16.7% |

-2.0% |

53.5% |

82.5% |

The headhaul East-West trade routes are key for liner profitability, and it is usual for freight rates to decline after Chinese New Year as container operators position themselves for the limited cargoes available. The implementation of additional bunker surcharges by container operators across all trade lanes since 1 January 2020 has also hidden any perceived negative impact of the virus. Additional surcharges on the Asia to North Europe trade are up to USD 300 per FEU (and vary per operator), and so this has significantly lifted all rates since the beginning of the year. On a year-to-date comparison basis (1 Jan to mid-March 2020 versus 2019), spot freight rates have remained strong, and in some cases have even increased, with the exception of the Shanghai to USWC trade lane. If we consider the year-on-year comparison, then spot freight rates have significantly increased across all trade routes in the table. These developments are counter-intuitive (certainly based on historical evidence) in the current weak market.

As well as the IMO 2020 impact, the main driver for the strong freight rates appears to be the resilience of the global players left in the market (now numbering about eight to ten). Liner operators appear to have finally seen that the only way to confront Black Swan events such COVID-19 is to resist any commercial inclination to reduce freight rates simply to fill empty slots. None of them want a repeat of 1H 2016 when the brutal freight rate war led to the eventual failure of Hanjin. Spot freight rates have even trended upwards in mid-March as operators look to enforce new general rate increases to ensure that all fuel costs are covered in the overall freight rate. In addition, it is clear that the blank sailing programmes have aligned supply and demand much more effectively, and our industry sources have advised that average vessel utilisation from Asia to Europe has on the whole been reasonably strong over the last month.

We understand that the Europe to Asia backhaul trade has experienced a significant uptick in freight rates in the last two to three weeks, driven by both strong demand from Asia, and the fact that there is limited space due to the high number of blanked sailings. Spot freight rates on this route have doubled since the beginning of the year to circa USD 1,100 per TEU as carriers have successfully implemented Peak Season Surcharges.

While we expect overall container operator earnings to be weak during 1Q 2020, this would appear (at least for the moment) to be driven more by a reduction in cargo volumes, than by low freight rates. We should not forget that all operators carry a mixture of spot and long-term contract cargo, and that this varies significantly between companies and trade lanes. Headhaul transpacific long-term contracts have not been concluded by operators yet, and for this year, these are likely to be delayed, adding further uncertainty for earnings in the near to mid-terms.

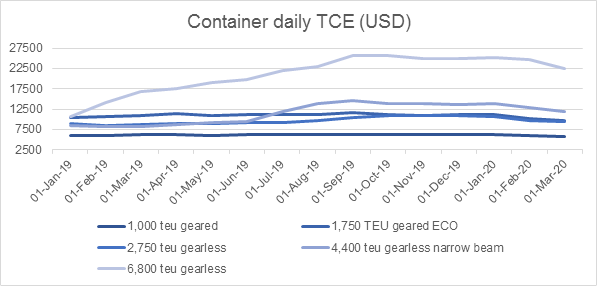

Unlike in other sectors, where there has been substantial volatility, TCE rates for container vessels in the main liquid market below 7,000 TEU, have been relatively stable over the last two months, as the graph below (sourced from Clarksons), illustrates.

Daily earnings for larger capacity container vessels have remained strong since September 2019 when more vessels started to enter Asian shipyards for scrubber retrofits. February and March are usually weak periods for vessel demand due to the Chinese New Year holidays, and so any negative impact of COVID-19 on vessel demand has not yet filtered into the charter market. While this is a positive for vessel owners, we are hearing more anecdotal reports that European feeder operators are running fewer services since there is less volume arriving in the market from China/Asia. On this basis, feeder operators may have fewer requirements from the charter market in the near-term for vessels of 2,000 TEU and below. Presently, demand for smaller capacity vessels in the intra-Asian trade routes is also understood to be weaker as the volume of semi-raw products moving from Chinese factories to South-East Asia has fallen in the last two months. This will also affect earnings for operators in an already ultra-competitive market where margins are thin.

Near-term Outlook

Notwithstanding the fact that we do not know how long the COVID-19 virus peak impact will last in Europe and the US, there are conflicting market views as to when a container recovery might happen. Reports indicate that Chinese factory production (of consumer goods) is increasing, and that port activity has returned to 70%-80% of “normal” levels, after seven weeks of near shut-down. However, industry sources have told us that factory production levels are only back to about 50%, which means that the earlier assertion is open to debate. If the level of factory production is correct, it is likely that container volumes will start to increase on China-export trades towards the end of March, but the supply chain issue now is how the major global consumption regions in Europe and the US are able to cope.

The rest of the world appears to be at least one month behind China in terms of the real virus impact on day-to-day life, and with so many people now working from home, this will likely affect orders for non-essential items as consumption declines. The ability for some functions in the supply chain, such as inland haulage and customs clearance may also be impacted as some of these duties cannot necessarily be carried out by home workers using a laptop. More importantly, and as happened in China, should (or when) factory workers in the US and Europe succumb to illness, then production of goods will also decline. Hence, one view is that there could be a significant initial spike in China exports in late March in order to fulfil vital near-term orders, but it could be short-lived. If pricing patterns follow historical trends, then liner operators will for a short period be able to increase freight rates significantly as demand for space tightens. This will certainly be the case for the shipment of foodstuffs carried in refrigerated containers.

However, as the virus impact likely manifests itself across Europe and the US (increasing in intensity as it did so in China), then this temporary resurgence in volumes may be halted once again until later during 2Q or 3Q 2020. It is certain that normal seasonal patterns in the container market will now be turned around.

After only a few months, the immediate impact on the liner sector appears to be manageable in that both freight rates and time charter earnings for owners have not been significantly impacted. The acid test for the container sector is how long the negative impacts of the virus will last in Europe and the US, and if the effects are more long-term, then some operators and owners may start to be more affected than others.

The significantly lower fuel prices will help container operators, and chartered-in tonnage can be returned to owners without renewing contracts. However, any sustained lower volumes will impact the sector, as vessels will remain idle (which remains a substantial cost). As mentioned, feeder operators are likely to be more impacted in the near-term as demand for vessel requirements could fall. However, on the positive side, when the genuine recovery in global shipments for vital consumer goods comes, there is the potential for earnings of global liner operators to climb rapidly. This will be exacerbated by the severe equipment imbalance, with not enough empty containers arriving back in Asia.

At the company level, all global container operators will be hit financially by the COVID-19 virus, although a few remain essentially State-backed (COSCO, HMM and Yang Ming), and so it could be argued, that the pressure on these companies is less. French operator, CMA CGM, has substantially more long-term debt than its peers due to its aggressive expansion, and combined with the COVID-19 impact, has significantly more risk to its revenues during 1H 2019 than its closest peers. MSC has a sizable cruise division which is feeling more financial pressure than probably any other maritime sector right now.

Overall, the container sector has not been hit quite as hard as other sectors in terms of revenue, although our view is that COVID-19 could potentially lead to further re-structuring should smaller liner companies (which may be subject to significant regional volume declines) fall into financial distress. Longer-term restructuring of vessel networks, and idling of vessels may result, and should this happen, tonnage providers will be hit the most as container operators will choose to utilise their own vessels as priority. Even if larger companies continue to be bailed out by State-aid, there is also the potentially negative knock-on effects for other sectors in the wider container supply chain, which includes freight forwarders. In addition, future investment or the ability to invest will likely be hit, and if we take the 2008/2009 global financial crisis as a historical comparison, newbuilding investment stopped for 18 to 24 months.