This week's Insight has come from Infospectrum alumnus Ian Staples, who has been keeping an eye on movements in the major South African coal export point, Richards Bay Coal Terminal (RBCT).

All long-lived FFA brokers out there would remember trading Capesize C4 with European power utilities, commodity traders and owner/operators. Do you remember C4? Probably not, but to jog your memory – it was the Richards Bay/ARA (more commonly referred to as Richards Bay/Rotterdam) Capesize voyage route for 150,000 metric tonne parcels (+/-10%), calculated in USD per tonne. The coal derivatives market also focused heavily on API2 and API4 swaps, one being FOB RBCT, the other being CFR ARA. Peas and carrots. Traders even created ‘synthetic freight’ by trading API2 vs API4, then sometimes spreading it against C4. No wonder traders, utilities, banks and brokers all loved this market with a passion. After all, to trade it you needed virtually no shipping knowledge.

From there morphed the C7 (Puerto Bolivar/ARA) trade, which was often spread against the C4, coupled with the rare beast of Average Timecharter trades (in USD/day). That was pretty much it for Capesize FFAs, but what a great market it was. One commodity, one ship type, pretty much one trade direction. I know that for me it didn’t feel like shipping, trading Morgan Stanley vs Goldman Sachs vs Constellation vs Enron vs Citibank.

Price moves East

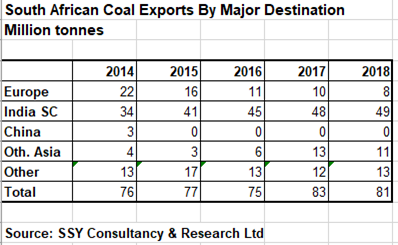

Then, like the meteor hitting Yucatan, something changed and nothing was ever the same again. The change was the price. Richards Bay coal stopped going to ARA. That was it. Gone. The utilities switched attention to C7 and 4TCs trades on physical and FFAs. The coal stopped going North and started heading East. API2 vs API4 was dead. The new norm for physical Richards Bay coal, shipped from RBCT, one of the most efficient load ports globally, with load rates of 30,000 per hour, was that 90% of coal went to Asia. The standard RB1 coal that is the premium grade exported from South Africa was required in China, but more so in India, South Korea and elsewhere.

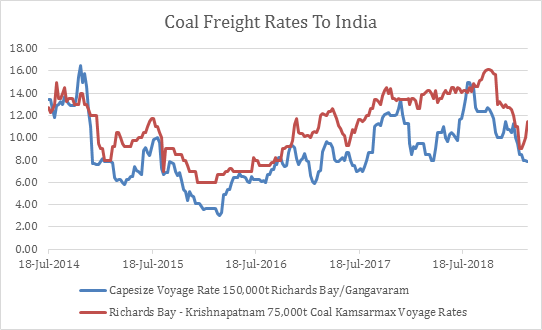

The Indian coal buying market has never been one to grasp derivatives with much gusto. Indian end-users want coal. Indian traders want to sell them coal. Anything else appears to be a lot less attractive. However, another phenomenon took hold. The old guard traders and banks were gone and those with relationships in Asia took over. The producers didn’t (and largely still don’t) have the marketing networks in the target markets. So sales from RBCT today are almost exclusively based on FOB contracts to traders that then do the shipping and deliver to end-users across Asia. The trade to India accounts for around 40% of RBCT exports, with 10% going to Europe, the rest dotted across Asia (South Korea being a major importer). It is worth noting that not one tonne of South African coal made it to China in 2018, a trend that exporters are sure will continue.

RBCT "101"

With the exception of Glencore, the major producers have almost no interest in shipping. They dig it up, rail it in, churn it out and get back home. To use RBCT, companies have to be a shareholder (of which there are currently 12). The allocation at the terminal is based on shareholding. Current shareholders include Anglo American, Exxaro, South 32, Kangra and others, which include an allotment for small Black Empowerment exporters.

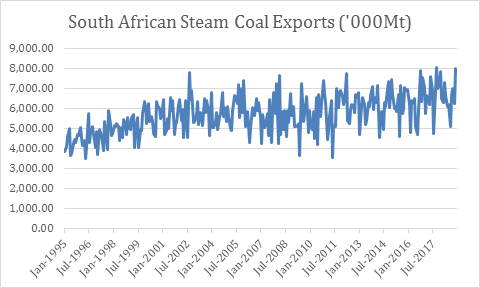

In numbers (for shipping, port and coal nerds), RBCT has six berths running along a 2.2km quayside in a sheltered bay. In 2018 the facility exported 73.5m Mt, down from the record year of 76.5m Mt, 82% of this went to Asian markets (none to China). Here’s where it gets complicated. The port says that it has a capacity to export 91m Mt per year – a figure that it has never been troubled. Despite the ‘close relationship’ with Transnet, it is widely acknowledged that this discrepancy in capacity and output is due to bottlenecks at Transnet rail links.

The State-owned rail links from the giant northern coalfields of Highveld, Witbank and Waterburg have not received much investment over the years. However, this is now changing. There is a raft of other numbers that slowly begin to create a picture of exports that is not one of success for RBCT. The draft maximum is 17.5m (with consideration for deeper vessels, but not much room for leeway). The port lost 36 days of loading due to bad weather in 2018 and 38 days in 2017. The swell, combined with the draft limits, appears to be the most consistent factor behind this. That means that the terminal lost close to 10% of loading time due to the weather. The port capacity of 91m Mt, less the balance for bad weather, takes it to 82m Mt per annum. Keen observers of statistics will note that this means the port only operated at just shy of 90% of weather-adjusted capacity. Those ‘in the know’ at RBCT say that this is going to be the norm going forward, so expect there to be a 10% reduction to whatever capacity is quoted.

The head of the port, Alan Waller, put the discrepancy between capacity and exports down to ‘market conditions’, namely South African coal being too expensive compared to Australian or Indonesian. But the loss of tonnes was not so high as to indicate that the mojo had been lost completely. One producer told me that it is ‘no issue’ to sell high grade coal, so more capacity should lead to more throughput. The facts do not seem to entirely bear this out though. The fact remains that there is little appetite for large-scale coal investments, so South Africa’s miners are looking anywhere and everywhere to find companies that are willing to finance mine production growth. The trader said that this trade growth for any new mining capacity that becomes available for export will likely have to come from new importers such as Pakistan and Bangladesh, rather than the more developed import markets in say India and South Korea. The trader also told me that the days of borrowing a little capacity from other RBCT shareholders are largely gone, and the method by which new exporters have ‘borrowed’ other companies’ allotments to get them into the market before trying to buy shares for themselves are also a thing of the past. ‘Spare capacity is now so expensive that it just makes no sense’, a trader told us.

There is also almost constant discontent with Transnet. The lobbying of coal producers to improve the rail capacity and remove bottle necks has borne some fruit. Transnet has announced that it will make rail improvements to connect better to existing coal fields, extend to new ones and are even considering pushing on into Botswana to make its vast coal reserves viable for export. A new tunnel to relieve a bottleneck and increase flow by up to three times is one of the centrepieces, alongside the usual dreary promises of ‘operational efficiencies’. Diverting non-bulk rail freight via a line through Swaziland is also planned. Fanciful stuff, especially when the numbers being talked about are as high as 25m Mt of extra rail capacity per annum.

What else drives the market?

The facts do sort of suggest something else is driving the market though. Fact one is that the port is not being used at full capacity today, even accounting for fact two, the increase of weather-related delays. Fact three is that ‘market conditions’ mean annual exports fell in 2018. Fact four, mature South African export markets like India are not really looking ripe for a sharp increase in coal purchases. Fact five, there won’t be enough investment capital to fund 25m Mt more production per year. Fact six, Transnet still has to deliver on its promises. Fact seven, there are no plans to expand the already busy port. You get the idea I’m sure.

It is not really possible to say that the coal market will contract in the coming years. It is not really possible to say that it will grow either. It is very likely that investments in coal production and coal-fired power will slow and environmental pressures will slow the growth. But who can say? What is true is that if Transnet does get the rail issues solved, and the miners find the investment capital, and the port can take the extra shipments, then it is going to be very busy at RBCT. 106m Mt of rail capacity, less the weather delays and 91m Mt of port capacity is going to be very stretched.

Where now for major exporters?

If the attitude of coal exporters is to be taken at face value, they are not hopeful of simply selling more to the same buyers. New markets have demonstrated that what they gain in import appetite, they lose in port infrastructure. In short, these are not Capesize markets. But if RBCT is going to be running at maximum capacity the problems will be magnified by smaller vessels arriving to load coal for Bangladesh for example. More traffic will mean more delays and less efficiency. It might turn out that rather than developing RBCT any further, that exporters could be better served developing the discharge port facilities, so that large vessels can load at RBCT and discharge in less developed locations. That development cost can be offset through long-term coal deals. With the majority of exports sold on an FOB basis it is also harder to co-ordinate with ships are arriving at the port, which is likely to make logistics an even greater headache. But then again, if the sales are FOB to traders then surely it is the traders who should pay for developments in discharge ports? Theoretical problems they may be, but if things do change then they will become real blocks to growth.

The conundrum for RBCT, its shareholders, Transnet, miners, coal traders, ship owners and operators are there for all to see. Go big? Go home? Go abroad? The possibility of Transnet building an empty railway is real, so is a congested port, but so is status quo whereby everybody likes to moan about things, but everything actually works better than the vast majority of world ports. It appears much of the outcome will depend on the future of the coal market and, as any seasoned RBCT observer will tell you, that can change on the flip of a coin.